Highlights

- 1 AI Models for Agriculture in Asia-Pacific

- 1.1 The Challenge: A Fragmented and Data-Deficient Landscape

- 1.2 The Solution: Foundational AI for Enhanced Harvesting

- 1.3 How It Operates: Data, Precision, and Google’s Distinct Advantage

- 1.4 The Tangible Impact: From Crop Yield to Access to Credit

- 1.5 An Expanding Ecosystem

- 1.6 A Global Vision, Originating in India

AI Models for Agriculture in Asia-Pacific

In a notable development highlighting the global scalability of India-first innovations, Google has announced the extension of its foundational AI models for agriculture to the broader Asia-Pacific region. The Agricultural Landscape Understanding (ALU) and Agricultural Monitoring and Event Detection (AMED) APIs, which have been supporting a network of startups and government agencies in India, are now being offered to trusted testers in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Japan.

These no-cost models utilize remote sensing and machine learning to deliver hyperlocal insights, aiming to tackle some of the most entrenched issues in agriculture. To delve into the technology, its implications, and the vision behind this expansion, discussions were held with Alok Talekar, Lead for Agriculture and Sustainability Research at Google DeepMind, and Avneet Singh, a Product Manager in Google’s Partner Innovation team.

The Challenge: A Fragmented and Data-Deficient Landscape

Agriculture, especially in a nation as extensive as India, is far from uniform. It’s a complex, fragmented ecosystem where solutions effective in one region may be entirely inadequate in another. This is the fundamental challenge Google aimed to tackle.

When posed with the crucial challenge his team identified, Alok Talekar stated that while “everybody wants to do the right thing, agriculture is very diverse in the country.” He noted that the necessary tools and access to information are often lacking.

Traditionally, agricultural data has been collected at a high level – district, block, or perhaps village. Avneet Singh pointed out that this level of detail is insufficient. He highlighted that “the right intervention and advisory is needed at an individual field level,” marking a significant gap that they aspire to fill.

Without field-specific data, decision-making becomes blunt and less effective. Talekar emphasized that there isn’t a universal solution. “What is accurate in Kerala may not apply in Bihar or Vietnam. Different local strategies are essential, underscored by a foundational layer of data that facilitates data-driven choices.”

The Solution: Foundational AI for Enhanced Harvesting

Rather than creating a single application, Google has introduced two foundational models that serve as a base layer for an entire ecosystem to build upon.

Agricultural Landscape Understanding (ALU)

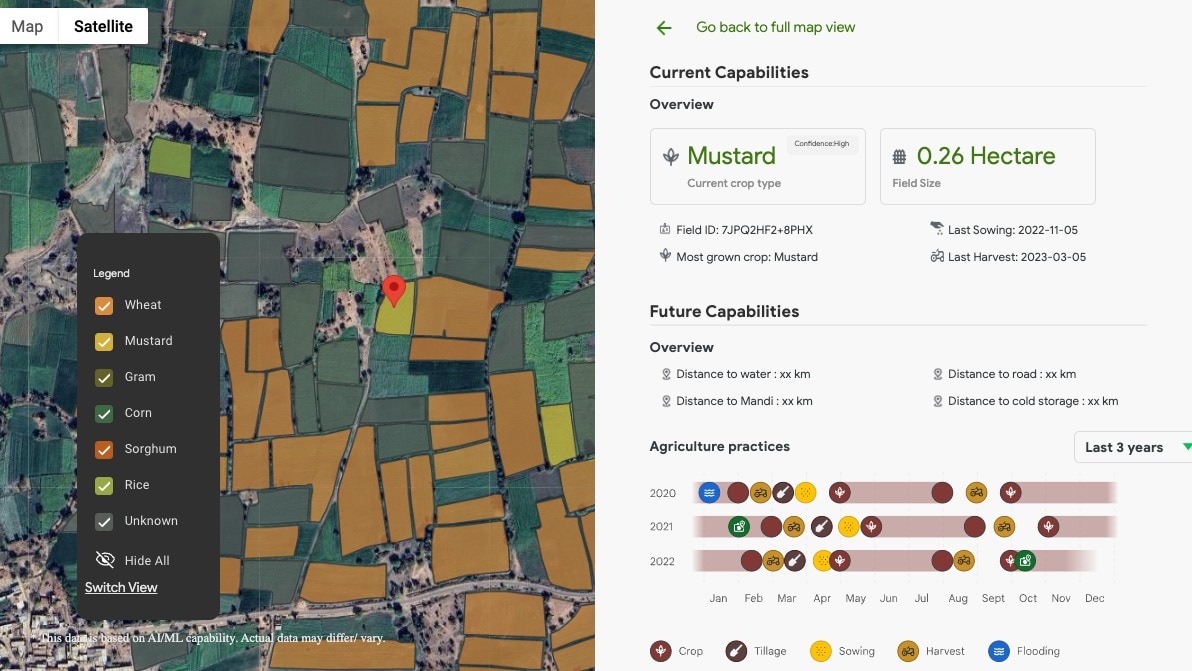

Launched in India in October 2024, this serves as the first layer. Avneet Singh explained that “ALU is our initiative to classify the agricultural landscape into various categories.” Through satellite imagery, it identifies and delineates individual fields, water bodies, and vegetation, ultimately creating a detailed digital representation of the agricultural landscape.

Agricultural Monitoring and Event Detection (AMED)

Building on ALU, the AMED API, introduced in July 2025, provides real-time insights. Singh elaborated that “this is where we begin analysing individual fields.” AMED can determine the current crop being cultivated, assess the field’s size, and monitor significant events like sowing and harvesting dates. Its data updates every 15 days, facilitating nearly real-time oversight.

Together, these models offer a rich, unbiased dataset that was previously unreachable. Talekar remarked that “we are unlocking a vast repository of data that was not available before.” He added that the launch marks the beginning of a journey, anticipating partnerships that will leverage this data.

How It Operates: Data, Precision, and Google’s Distinct Advantage

Sustaining these models is an extensive collection of geospatial data. Talekar clarified that “all of these models rely heavily on earth observation data, mainly derived from satellite imagery, whether public or licensed satellite imagery used by Google.”

He noted that Google’s long-standing investment in geospatial technologies like Google Maps presents a unique edge, unlocking opportunities that were once the purview of large agricultural firms for smallholder farmers.

However, with AI, precision and bias are constant considerations. Talekar candidly discussed the hurdles. He acknowledged that “any model functioning on such a grand scale is unlikely to be perfectly accurate everywhere. It’s possible to pinpoint fields where the system falters.” The critical question is the statistical accuracy required at scale to make it beneficial, which he believes needs to be evaluated for each specific use case.

To ensure the models are practical, Google implements a multi-layered validation approach, encompassing standard machine learning evaluations, comparisons with aggregate government census data, and independent spot checks by third parties like the startup TerraStac and the Government of Telangana.

The Tangible Impact: From Crop Yield to Access to Credit

How does this technology assist a farmer unfamiliar with APIs or AI? The benefits manifest through ecosystem partners that leverage Google’s models.

Avneet Singh shared a hands-on example: an AgriTech company designed to assist farmers optimise crop yields. They can scale to identify fields with specific crops at any district, block, or region, delivering targeted interventions. The API provides details on when the crop was sown and its historical context, facilitating highly precise advice.

Perhaps most notably, the technology influences financial access. Alok Talekar illustrated the present lending landscape for many farmers. He explained that “they often cannot approach banks directly, as the verification costs for the bank to ascertain that a farmer is indeed cultivating crops are too steep. The expense of sending someone to verify is comparable to the loan amount in many cases.” This situation drives farmers toward secondary markets with exploitative loan rates.

Google’s models present a solution through an unbiased, cost-effective method to verify agricultural activities, lessening risks and costs for financial institutions and potentially unlocking fair and accessible credit for millions. For instance, in India, the fintech company Sugee.io is currently integrating insights from the APIs to enhance loan application processes and management.

An Expanding Ecosystem

In India, these models are already being employed across various critical initiatives:

Krishi DSS: The ALU and AMED APIs are being integrated into this national platform for the Department of Agriculture, assisting policymakers in making knowledgeable decisions.

Government of Telangana: The state employs the models on its AdEx platform, which serves as an open data exchange for agricultural solutions.

Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW): This think tank intends to utilise the APIs to establish a new mechanism for differentiated income support, encouraging farmers to shift towards more environmentally friendly crops.

A Global Vision, Originating in India

The triumph of this ecosystem-centric model in India propels its expansion to Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Japan.

In the official announcement, Talekar expressed excitement about the potential impact across the APAC region, stating that the aim is to replicate the success seen in India. This reflects a firm belief that solutions addressing India’s most pressing agricultural challenges can also serve the rest of the world.

When queried about data privacy, Singh assured that all data is strictly geospatial and does not include Personally Identifiable Information (PII). He confirmed that “there is no ownership structure within this,” ensuring the protection of farmers’ privacy.